Threat Hunting Basics

Threat hunting is the proactive practice of searching for hidden threats or malicious activity within an organization’s environment, before or sometimes after alerts are triggered. Its main goal is to uncover attacks early, reducing the dwell time, which is the period an adversary remains undetected in the network.

Dwell time refers to the period an attacker remains undetected in your environment. Minimizing dwell time is critical because even a few hours of undetected activity can lead to stolen credentials, lateral movement, and data exfiltration.

Why Traditional Security Tools Fall Short

While AV and EDR solutions are valuable, they inherently rely on predefined detection rules such as known file hashes, signatures, or behavioral indicators. These tools are excellent at catching known threats but often fail against:

- Zero day malware that has never been seen before

- Advanced Persistent Threats (APT) employing novel techniques

- Insider threats or misconfigurations that behave like legitimate activity

Traditional security tools are fundamentally reactive. If a malicious action does not match a signature or known behavior, it can easily go unnoticed. Threat hunting fills this gap, enabling security teams to actively search for anomalies, uncover stealthy attacks, and improve detection over time.

The Value of Threat Hunting

Threat hunting goes beyond simply finding malware or malicious IPs. It allows security teams to uncover critical weaknesses that may otherwise remain hidden, such as:

- Misconfigured devices that could be exploited

- Unpatched software on critical servers

- Unauthorized or suspicious software installations

- Evidence of privilege escalation or unauthorized account activity

In addition to immediate detection, hunting provides insights that improve overall security posture. Every hunt refines detection rules, enhances log collection practices, and informs proactive risk mitigation strategies.

When Should You Hunt?

Threat hunting can be initiated in multiple scenarios. Some hunts are scheduled periodically to ensure no anomalies go unnoticed, while others are reactive to intelligence or internal alerts. Common triggers include:

- Routine proactive hunts within organizations that maintain dedicated hunting teams

- New threat intelligence indicating emerging attacks targeting your sector

- SOC or IR alerts highlighting suspicious activity that requires deeper investigation

- Findings from previous hunts, where anomalies were identified but not fully investigated

- Post-risk assessment validation, focusing on high value systems or sensitive data

Effectively, threat hunting is both a strategic and tactical process, balancing routine assessments with intelligence driven investigations.

The Threat Hunting Lifecycle

A successful threat hunt follows a defined lifecycle, which ensures both structure and repeatability:

- Trigger: Define why the hunt is happening. This usually takes the form of a hypothesis, informed by intelligence, risk assessments, or anomalies.

- Investigation: Dive into internal telemetry collect logs, analyze network traffic, and validate the hypothesis against real world data.

- Resolution: Conclude the hunt by documenting findings, feeding insights into SIEM rules, and updating playbooks for future hunts. Post hunt analysis often leads to new hypotheses and detection improvements.

Types of Threat Hunts

Threat hunting is not one-size-fits-all. Different hunts focus on different sources of intelligence and methodologies:

Structured Hunts

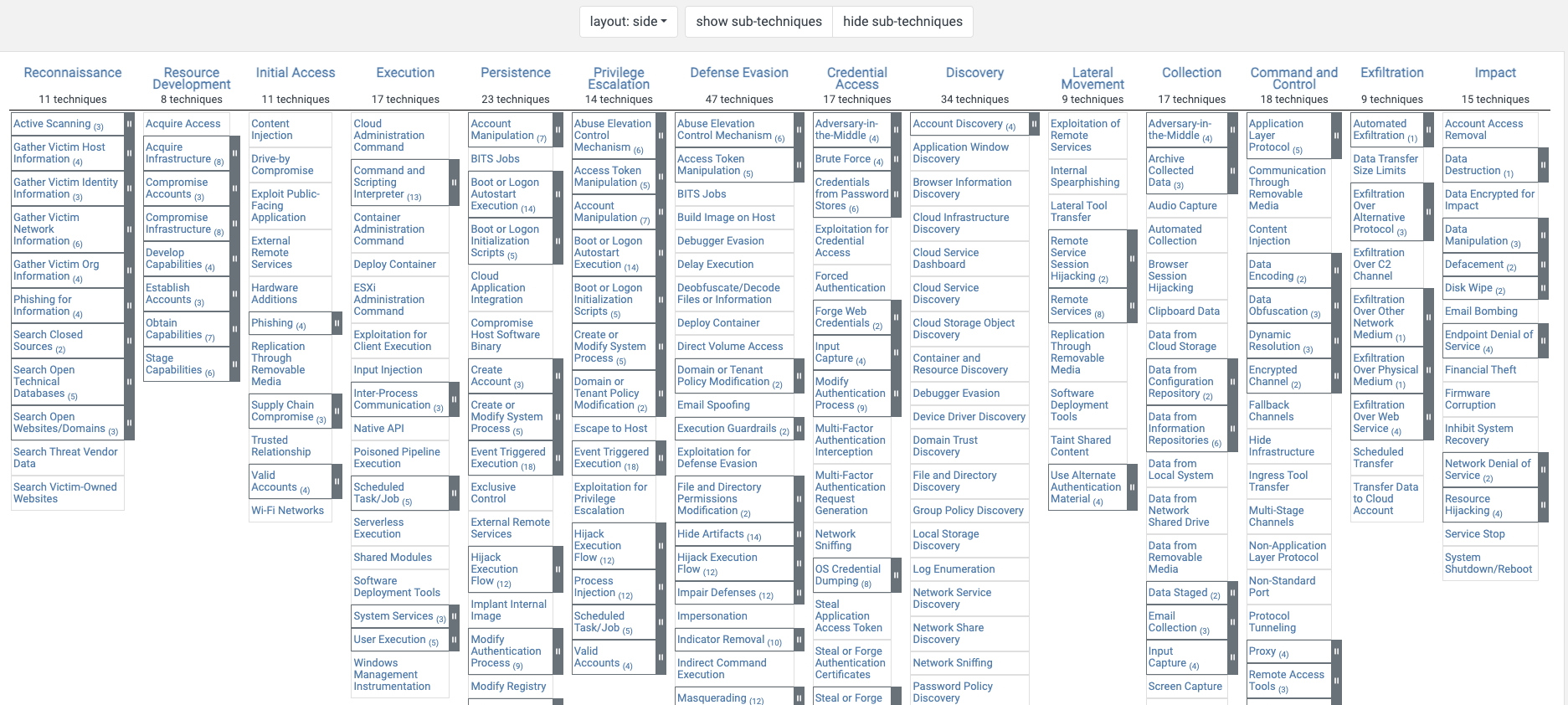

Structured hunts focus on known adversary TTPs (Tactics, Techniques, Procedures), often derived from frameworks like MITRE ATT&CK. Instead of searching for specific indicators, structured hunts focus on behavioral patterns that attackers are likely to use. For example, a hunter might look for evidence of lateral movement or persistence techniques even if no known malware is detected.

Unstructured Hunts

Unstructured hunts are typically IOC driven, beginning with indicators of compromise obtained from threat intelligence, previous incidents, or alerts from SOC/IR teams. These hunts involve searching logs and telemetry for any activity that matches these known indicators, and can reveal early stage intrusions or stealthy activity.

Situational Hunts

Situational hunts target high value systems or assets identified as high risk. For example, a public facing customer portal with sensitive data may be the focus. Hunters analyze deviations from expected behavior, such as unusual login patterns, access from unexpected geolocations, or abnormal file access.

The Pyramid of Pain

The Pyramid of Pain is a concept that helps hunters prioritize the value of indicators:

| Indicator Type | Hunting Impact |

|---|---|

| Hash Values | Easy to detect, but attackers can easily change them |

| IP Addresses | Moderately valuable; attackers can rotate IPs |

| Domain Names | Harder to change; requires registration and hosting effort |

| Network/Host Artifacts | Attacker must modify tactics or infrastructure; valuable detection points |

| Tools | Disrupts adversary operations; forces new tools or methods |

| TTPs | Most valuable; behavior based detection forces attackers to change techniques |

Focusing on TTPs and behaviors rather than just atomic indicators is the key to hunting beyond the basics.

Cyber Kill Chain

Hunting is often mapped to the Cyber Kill Chain, which breaks down the stages of an attack. Understanding each phase allows hunters to anticipate adversary activity and focus on detection opportunities.

| Phase | Threat Hunting Relevance |

|---|---|

| Reconnaissance | Information gathering; often subtle or invisible in logs |

| Weaponization | Payload creation; typically undetectable until delivered |

| Delivery | First observable phase, e.g., phishing email or USB drop |

| Exploitation | Payload execution, privilege escalation, lateral movement |

| Installation | Backdoor installation and persistence setup |

| Command & Control | C2 communication; hunters can capture anomalous traffic |

| Actions on Objectives | Data exfiltration or destruction; final adversary goal |

By aligning hunts to this framework, hunters can prioritize investigations and anticipate adversary behavior.

MITRE ATT&CK Mapping

MITRE ATT&CK provides a structured library of adversary behaviors, enabling hunters to map activities to tactics and techniques. Mapping hunts to ATT&CK:

- Improves detection coverage across systems

- Allows reusable detection queries and rules

- Provides a common language for threat intelligence and incident response teams

Threat Hunting Methodologies

Intelligence Driven Hunting

Intelligence driven hunting starts with threat intelligence to formulate a testable hypothesis. For example, if a vendor report indicates a specific APT is targeting your industry using DLL search order hijacking, a hunter might query endpoint logs for suspicious DLL loading patterns.

Data Driven Hunting

Data driven hunting relies primarily on internal telemetry to identify anomalies. Patterns such as repeated failed logins, unusual PowerShell execution, or abnormal data transfers can reveal threats even before intelligence indicators are available.

Knowledge Based Hunting

Knowledge based hunting depends on deep expertise. Hunters leverage their understanding of network architecture, endpoints, normal baselines, and known adversary TTPs to formulate hypotheses and detect sophisticated activity. This approach is often used to identify emerging threats or sophisticated attacks that evade traditional detection.

Data Collection & Log Management

Comprehensive data collection is the backbone of threat hunting. Key sources include:

- Endpoint logs: Sysmon, PowerShell, Windows Event Logs, application logs

- Network telemetry: Netflow, proxy, firewall, DNS, packet captures

- Cloud & SaaS logs: CloudTrail, GCP logs, remote access portals

Proper log retention, normalization, and enrichment are critical. Tools like Splunk, ELK Stack, and Velociraptor help aggregate telemetry, making it actionable for hunts.

IOC Correlation

Raw IOCs are often insufficient in isolation. Correlating indicators across time, source, and tools provides context and actionable intelligence. Correlation techniques include:

- Exact Matching: Matching IPs, hashes, or domains across multiple feeds

- Infrastructure Pivoting: Mapping related infrastructure to reveal hidden links

- Fuzzy Matching: Detecting near identical malware or lookalike domains

- Time Based Correlation: Reconstructing events to visualize attack progression

- TTP and Campaign Linking: Mapping behaviors to known adversaries

Endpoint & Network Threat Hunting

Endpoint hunting focuses on detecting anomalies at the system level, including:

- Suspicious process execution and parent child relationships

- Unauthorized registry or service modifications

- Malicious scheduled tasks

- Unusual PowerShell or script activity

Network hunting emphasizes protocol misuse, anomalous traffic patterns, and abnormal volumes, often leveraging packet captures and telemetry from firewalls, proxies, and IDS/IPS systems.

Sysmon Event IDs for Threat Hunting

Sysmon provides high fidelity telemetry for endpoint monitoring. Key event IDs for hunters include:

| Event ID | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Process creation; monitor parent-child relationships and commands |

| 2 | File creation time changes; detect timestomping attempts |

| 3 | Network connections; track C2 and suspicious outbound activity |

| 5 | Process termination; observe abnormal lifecycles |

| 6 | Driver loaded; detect unauthorized driver insertion |

| 7 | Image loaded; monitor DLLs for malicious injection |

| 8 | CreateRemoteThread; potential code injection activity |

| 10 | Process access; detect privilege escalation attempts |

| 11 | File creation; monitor unusual or hidden files |

| 12 | Registry value change; track persistence modifications |

| 13 | Registry value deletion; detect tampering or evasion |

| 14 | Registry value rename; identify stealthy modifications |

| 15 | File stream creation; monitor for alternate data streams |

| 22 | DNS query; detect suspicious external lookups |

These events form the foundation for behavioral threat detection, enabling hunters to detect activity beyond simple signatures or IOCs.

Using Splunk for Endpoint Threat Hunting

The goal here is not to learn Splunk as a product, but to understand how Splunk can be used to support endpoint threat hunting by querying, correlating, and pivoting across endpoint data.

SPL in the Context of Threat Hunting

Splunk uses Search Processing Language (SPL) to retrieve and process data. From a threat hunter’s perspective, SPL is simply a way to ask structured questions of endpoint logs.

Some SPL concepts are fundamental when hunting:

Index

All data in Splunk is stored in indexes. Selecting the correct index is the first scoping decision in any hunt. An overly broad index introduces noise, while an overly narrow one can cause blind spots.Sourcetype

Sourcetypes describe the kind of data being searched, such as Windows Security logs, Sysmon logs, or PowerShell logs. Using the correct sourcetype helps narrow the dataset early in the search.Filters (

field=value)

Filters specify conditions events must meet. Hunters use filters to isolate behaviors of interest from normal endpoint activity.Pipes (

|)

Pipes pass the output of one command to another. This allows raw event searches to evolve into analytical queries.- Commands

Commands define how Splunk processes retrieved events. Commonly used commands during hunts include:tableto format resultsstatsto aggregate behaviorsortandtopto identify outliersdedupto remove duplicate events

- Raw vs transforming searches

Raw searches return individual events and are useful during early investigation. Transforming searches summarize data and help identify patterns or anomalies.

Basic Endpoint Oriented SPL Examples

A simple Windows Security log search might look like:

1

index=main sourcetype="WinEventLog:Security" host="CLIENT" EventCode=3

This retrieves specific events from a single endpoint. Such searches are typically used to gain initial visibility before refining the hunt.

PowerShell activity is a frequent focus during endpoint hunts due to its extensive abuse by attackers. Script block logging provides deeper visibility:

1

2

index=main host="CLIENT" EventCode=4104

| search Message="Invoke-WebRequest" OR Message="iwr" OR Message="iex"

This query looks for PowerShell commands commonly used to download or execute payloads. The intent is not to immediately label this activity as malicious, but to identify executions that warrant closer inspection.

Building Queries Using Hypotheses

Effective threat hunting starts with a hypothesis, not a query.

For example:

Attackers are executing suspicious scripts from temporary directories.

This hypothesis can be explored by searching for:

- PowerShell scripts executed within a defined timeframe

- Files launched from

C:\Windows\TemporC:\Temp - Script files created in temporary locations shortly before execution

Splunk allows hunters to explore each of these paths independently and pivot as new evidence emerges.

Common Endpoint Hunting Queries

New User Creation

Unexpected user creation events may indicate persistence or unauthorized access.

1

index=main source="WinEventLog:Security" EventCode=4720

These events are typically correlated with subsequent logons, privilege changes, or unusual account usage.

Brute Force Authentication Attempts

Brute force attacks often appear as multiple failed logons followed by a successful one in a short period.

1

index=main (EventCode=4625 OR EventCode=4624) | stats count(eval(EventCode=4625)) as Failure, count(eval(EventCode=4624)) as Success by ComputerName, Account_Name | where Failure > 5 AND Success > 0 | table _time, Account_Name, Success, Failure

This query aggregates authentication behavior by account and system, helping identify potential credential compromise.

Unexpected Network Connections

Outbound connections from endpoints can reveal command-and-control traffic, lateral movement, or data exfiltration.

1

2

index=main EventCode=3

| table _time, ComputerName, SourceIp, DestinationIp, DestinationHostname, DestinationPort, Image

During a hunt, suspicious destinations or uncommon parent processes become pivot points for deeper analysis.

Suspicious PowerShell Activity

Encoded PowerShell commands are often used to obscure malicious intent:

1

2

index=main EventCode=4104

| search Message="encoded"

Download and execution patterns are also common indicators:

1

2

index=main EventCode=4104

| search Message="Invoke-WebRequest" OR Message="iwr" OR Message="iex"

These queries surface PowerShell activity that may be associated with payload staging or execution.

Hunting for Persistence on Endpoints

Persistence mechanisms tend to leave durable artifacts, making them valuable hunting targets.

Scheduled Tasks and Services

1

index=main (EventCode=7045 OR EventCode=4698)

This query identifies newly created services or scheduled tasks, which attackers frequently use to maintain access.

Registry-Based Persistence

1

2

index=main EventCode=12 EventType=CreateKey TargetObject="HKLM\System\CurrentControlSet\Services\*"

| table _time, User, Image, TargetObject

This surfaces registry keys related to service creation. Unusual service names, paths, or user contexts often warrant further investigation.

Practical Considerations When Hunting in Splunk

- Ensure the selected time range aligns with the scope of the hunt.

- Format results using

tableto make manual analysis easier. - Use

stats,count,sort, andtopto summarize behavior. - Use

whereto refine results andevalto create or rename fields when needed.

Example Endpoint Hunt Workflow

Consider a scenario where an attacker uses PowerShell to download malware using encoded commands. An initial query using Sysmon process creation logs might be:

1

index=sysmon EventCode=1 Image="powershell" CommandLine="enc"

Once suspicious executions are identified, the hunt can be refined:

1

index=sysmon EventCode=1 Image="powershell" CommandLine="update.ps1"

Correlating with Windows process creation events adds context:

1

index=wineventlog EventCode=4688 New_Process_Name="powershell" Command_Line="update.ps1"

Formatting the results improves readability:

1

2

index=sysmon EventCode=1 CommandLine="update.ps1"

| table _time, Computer, Image, CommandLine, Hashes

Finally, hashes extracted from these events can be used to pivot further:

1

2

index=sysmon EventCode=1 Hashes="<hash>"

| table _time, Computer, Image, CommandLine, User, Hashes

Threat Hunting with ELK

Most threat hunting activities eventually come down to one thing: how effectively you can search and correlate telemetry. In environments where ELK is used as the central logging platform, understanding how its components work together and how to query them properly becomes critical for successful hunts.

ELK Stack in a Threat Hunting Context

The ELK stack is made up of three primary components, each playing a distinct role in the hunting workflow:

Elasticsearch

Acts as the backend where logs are indexed, stored, and searched. This is where the actual hunting happens fast searches, correlations, and aggregations over large datasets.Logstash

Responsible for ingesting, parsing, and transforming logs before they are indexed. Proper parsing here directly affects hunt quality; poorly structured fields make effective hunting difficult.Kibana

The interface hunters interact with used for searching, filtering, visualizing events, and building dashboards.

In most environments, Beats are also involved:

- Winlogbeat, Filebeat, etc., are used to ship logs from endpoints and servers into the stack.

- Conceptually, Beats in ELK serve a similar role to Splunk Forwarders in Splunk-based setups.

From a hunter’s perspective, the key takeaway is this:

The quality of your hunts depends heavily on what logs are collected and how well they are structured.

Searching in ELK

ELK supports multiple query languages, but two are especially useful for threat hunting: KQL and EQL.

Kibana Query Language (KQL)

KQL is commonly used for quick, interactive searches and filtering during exploratory hunts.

Key characteristics:

- Simple, readable syntax

- Field-based matching

- Fast for ad‑hoc analysis

Common features:

- Field matching using

: - Boolean logic (

AND,OR,NOT) - Wildcards for partial matches

- Easy field selection for narrowing down results

Best practices for hunting with KQL:

- Prefer field-based searches over full-text searches

- Save commonly used hunt queries

- Start broad, then progressively narrow down

Examples:

1

2

event.code:11 AND "*ps1*"

winlog.channel:"Security" AND (winlog.event_id:4688 OR winlog.event_id:4698)

KQL is ideal when you’re validating hypotheses, pivoting quickly, or trying to understand what “normal” looks like before drilling deeper. Elasticsearch Query Language (EQL) EQL is designed for event correlation and multi-step attack detection, making it extremely powerful for advanced threat hunting. Where EQL shines:

- Correlating related events

- Detecting attacker tradecraft across time

- Modeling attack chains instead of single events

- Basic structure:

- event_type where condition. Example:

1

process where process.name == "powershell.exe"

- event_type where condition. Example:

EQL supports logical operators such as:

1

==, !=, <, >, and, or, not

Sequences

- Sequences allow hunters to express attacker behavior as “this happened, then that happened”:

1 2 3

sequence by host.name with maxspan=5m [process where process.name == "cmd.exe"] [network where destination.port == 4444]

This is particularly useful for detecting living-off-the-land attacks, lateral movement, and command-and-control activity.

Common Hunt Queries (Starting Points)

Some common patterns hunters often look for include:

- Suspicious Account Activity

event.code:4848 - Suspicious Process Behavior

event.code:1 - Unexpected Outbound Network Connections

event.code:3 - Suspicious PowerShell Activity

- Encoded commands

(event.code:4103 OR event.code:4104) AND message:"*encoded*" - Downloads and execution

(message:"*Invoke-WebRequest*" OR message:"*iwr*" OR message:"*iex*")

- Encoded commands

- Persistence Mechanisms

- Scheduled tasks

event.code:4688 AND "schtasks.exe" - Malicious services

event.code:4697 OR event.code:7045

- Scheduled tasks

These queries are not meant to be definitive detections, but rather starting points for investigation and pivoting.

Example Hunt: Credential Access via SAM Dump Consider a scenario where an attacker dumps the SAM database to extract password hashes and later perform a Pass‑the‑Hash attack.

- Step 1: Identify Relevant Logs

- Windows Security Logs

- PowerShell Script Block Logs

- Sysmon Logs

- Step 2: Build Initial Queries

1 2 3

winlog.event_data.Image:"*reg.exe*" AND winlog.event_data.CommandLine:"*save*" AND winlog.event_data.CommandLine:"*\\HKLM\\SAM*"

- Step 3: Analyze and Pivot

- If you observe suspicious activity, pivot into related areas:

- Credential dumping tools

winlog.event_data.CommandLine:("*procdump.exe*" OR "*mimikatz.exe*") - NTLM-based authentication

event.code:4624 AND message:"*ntlm*" - Lateral movement tools

1 2 3 4 5

winlog.event_data.CommandLine:("*wmic.exe*" OR "*psexec.exe*" OR "*smbexec.py*") AND NOT winlog.event_data.User:"*SYSTEM*" Suspicious parent-child process relationships winlog.event_data.ParentImage:"*wmiprvse.exe*" AND winlog.event_data.CommandLine:("*cmd.exe*" OR "*powershell.exe*")

- Credential dumping tools

- If you observe suspicious activity, pivot into related areas:

Conclusion

Threat hunting is both an offensive and defensive approach for identifying anomalies. By combining intelligence driven, data driven, and knowledge based approaches, hunters can proactively detect sophisticated adversaries. Coupled with robust telemetry, proper IOC correlation, and MITRE ATT&CK mapping, organizations can significantly reduce dwell time and strengthen their security posture.